So, When Does Rev. Al Sharpton's Suspension Begin?

Like Brian Williams, MSNBC host's lies deserve review

FEBRUARY 11--With its swift and severe punishment of Brian Williams, NBCUniversal declared yesterday that it will not stand for on-air talent lying to viewers.

Now that the media conglomerate has delineated that bright line, when does the Rev. Al Sharpton’s  suspension without pay begin?

suspension without pay begin?

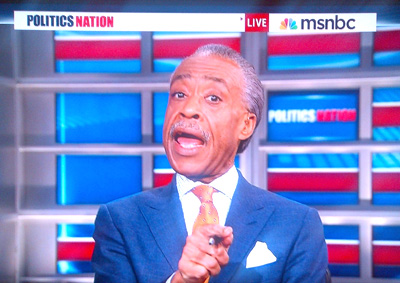

In the wake of last year’s lengthy TSG report about Sharpton’s secret work as a paid FBI Mafia informant, the MSNBC host sought to blunt the story’s disclosures with a series of lies told at a pair of press conferences, on his nightly “Politics Nation” program, and in a report on Williams’s own NBC Nightly News (which was rebroadcast on NBC's Today show).

Sharpton, 60, cast himself as a victim who first ran into the FBI’s warm embrace when a scary gangster purportedly threatened his life. He was “an American citizen with every right to call law enforcement” for protection, Sharpton told his MSNBC audience. His sole motivation was to “try to protect myself and others.”

He needed the FBI’s help, Sharpton claimed, because his relentless advocacy on behalf of African-American concert promoters had angered wiseguys with hooks in the music business. “I did the right thing working with the authorities,” Sharpton assured viewers. As for being branded an informant, that was a label for others to worry about. “I didn’t consider myself, quote, an informant. Wasn’t told I was that,” said Sharpton.

These claims, broadcast by NBCUniversal, were demonstrably false.

Sharpton was, again, lying about when, how, and why he became a government informant. This historical rewrite was intended to cast his  cooperation in the most favorable--even heroic--light possible. The true story, however, was grimier and far less commendable.

cooperation in the most favorable--even heroic--light possible. The true story, however, was grimier and far less commendable.

Sharpton was once an organized crime associate who got caught up in an FBI sting and immediately agreed to join Team America to stay out of prison. The street-smart preacher’s decision to become an informant was borne out of fear and a desire for self preservation, a calculus not unique when someone is cornered by men with badges.

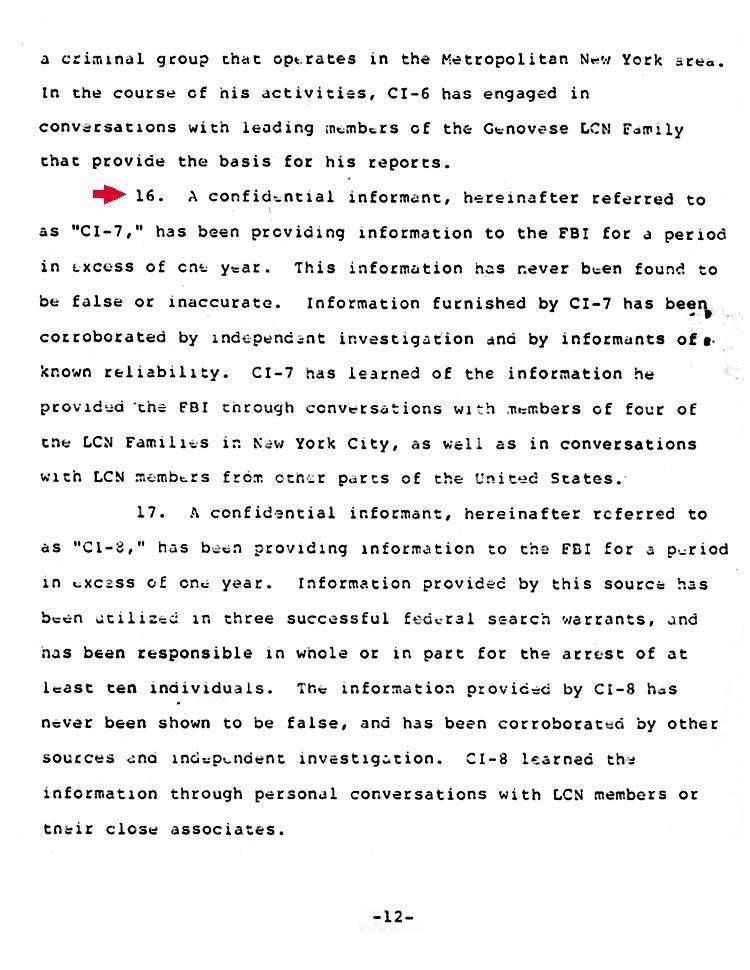

Now, if NBCUniversal cared to examine the televised claims Sharpton has made about his work as an informant, the company’s newly formed internal affairs division could review hundreds of pages of FBI documents chronicling Sharpton’s work as “CI-7,” short for confidential informant #7, and they could track down members of the FBI-NYPD organized crime task force for which Sharpton surreptitiously recorded his meetings with gangsters.

And company brass would certainly want to review the first story to expose Sharpton as a snitch, a January 1998 Newsday piece authored by a Murderers Row of reporters: Bob Drury, Robert Kessler, Mike McAlary, and Richard Esposito. If that last guy’s name rings a bell, well, it is probably because Esposito--now senior executive producer of NBC's investigative unit--is heading the network’s review of Williams’s Iraq War and Hurricane Katrina claims.

Could there be a better man to head the Sharpton Task Force? Luckily, Esposito’s memories of Sharpton’s FBI activities remain clear, as evidenced by a article (“Rev. Al Sharpton and Me”) he wrote for the NBC News web site the day after TSG published  its Sharpton story last April.

its Sharpton story last April.

As detailed by TSG and Esposito (seen at right) and his Newsday colleaugues, Sharpton agreed to become an informant after he was secretly videotaped discussing a possible cocaine deal with an undercover FBI agent.

Sharpton was “flipped” on a Thursday afternoon in June 1983 when he showed up at a Manhattan apartment expecting to meet with a former South American druglord seeking to launder money through boxing promotions (like those handled by Sharpton pal Don King). The role of "druglord" was played by undercover FBI Agent Victor Quintana.

After Sharpton entered the apartment, FBI Agents Joseph Spinelli and Kenneth Mikionis emerged from the bedroom. They then played Sharpton a videotape of a prior meeting with Quintana during which cocaine was a topic of conversation. While the agents were unsure whether Sharpton had said enough to warrant a criminal prosecution, the civil rights activist had no doubt he was in trouble. Sharpton agreed on the spot to begin working as an informant.

The following day, at Spinelli’s direction, Sharpton recorded the first of several conversations with King, a major FBI target.  Sharpton, of course, has repeatedly lied when asked whether he made such consensual recordings for his FBI handlers.

Sharpton, of course, has repeatedly lied when asked whether he made such consensual recordings for his FBI handlers.

Over the next several years, Sharpton worked with FBI agents and NYPD detectives as they put together criminal cases against leaders of the Genovese organized crime family. For example, he used a briefcase outfitted with a hidden recording device to tape ten meetings with a Gambino crime family figure named Joseph Buonanno.

In sealed court filings, federal investigators lauded “CI-7” as a reliable, productive, and accurate source of information about mobsters. The FBI noted that its informant gathered information about La Cosa Nostra matters through his contact with members of four of New York’s five mob families and via “conversations with LCN members from other parts of the United States.”

About nine months into his work as an informant, Sharpton was purportedly threatened by Salvatore Pisello, a mob associate affiliated with MCA Records in Los Angeles. Pisello, Sharpton claimed in his autobiography, was angry that the activist was agitating to have African-American promoters included in the “Victory Tour” starring Michael Jackson and his brothers. Presumably, such involvement by these promoters would have cut into Pisello’s piece of the lucrative tour.

The reported threat, however, amounted to nothing but talk. Sharpton, however, has cast the incident--for which he is the sole witness--as the motivation for him approaching FBI agents for some federal succor.

While Sharpton’s sleight of hand when it comes to matters temporal and factual is well established, he chose to boldly use the airwaves of NBCUniversal--his employer--to broadcast lies about his tawdry past.

Unlike Williams, however, viewers should not expect an apology--even a mangled one at that--from Sharpton.